|

Almost

every child is born a cartoonist.

At

the age of two you know how to reduce a drawing to a

few simple lines. You know how to lay out a page to

make a coherent whole. You know how to chose colors

to express an emotion rather than give a photographic

reproduction of reality. You know how to draw a face

that expresses a certain personality. You know how to

make a picture tell a story.

|

Then

the attack begins. Your parents, your teachers,

your psychotherapists (if you can afford them)

begin the lifelong struggle to cure you of being

you. Eventually your classmates enlist on the

enemy side.

Most

of us surrender fairly early in the war. I didn't.

The adults wanted me to adopt a lifestyle based

on competitive sport. I wanted to adopt a lifestyle

based on drawing. I began by not wanting to compete

with other children in games. That meant I was

hanging around the house with nothing to do.

One

day my father was working at home and I kept distracting

him by asking questions. Finally he sat me down

in a sunny windowseat, gave me a crayon and a

ream of typewriter paper, and said, "Keep busy!"

I grasped the crayon like a dagger and slowly

dragged it across the paper. Then I looked at

the mark I had made like God looking at the universe

He had created and found it good. I made another

mark, then another. They too were good. I flailed

my arms with excitement. Those were my own marks.

I myself had made them. A kind of trance came

over me and I drew and drew and drew until evening

came on. I did not realize until I became an adult

that what I was drawing was the proverbial mark

in the sand.

Since

that day I have never let anything stop me from

drawing. The first day of kindergarten arrived

like the crack of doom. At Physical Education

time the "coach" lined up all the boys in my class,

about twelve of us, at one end of the playground

and pointed to the other end of the playground.

|

|

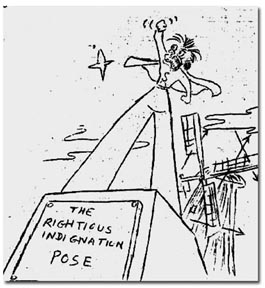

| Some

of Ray's early work from "Space Warp" |

|

Said

he, "Now we're going to run a little footrace here.

I'm going to count to three and then say go. When I

say go you guys are going to run as fast as you can

and see who can get to the gate first. He'll be the

winner. The last one to get to the gate will be a rotten

egg." I looked over my competitors and figured the odds.

One chance to be a winner. Eleven chances to be a loser,

including one to be a rotten egg. Some of my classmates

looked pretty hunky, easily more muscular than me. The

coach counted. "One, two, three, go!" Eleven boys ran

like crazy. One boy, me, just stood there.

"Let's

try that again," said the coach. He lined us up again and

counted down again, but this time he gave me a little shove.

Eleven boys ran. One, me, didn't. He looked at me, face brick-red

with fury and growled, "I'll tell your teacher." But my teacher

couldn't get me to run, the principal couldn't get me to run,

my parents couldn't get me to run, my parents' psychotherapist

couldn't get me to run, the sergeants at three years of military

school couldn't get me to run.

As

I write I have recently turned seventy years old. I still

haven't run. I had learned what no child is supposed to learn,

that if you say yes to the game you can, at best, win out

against a ragtag troop of little kids your own age. If you

say no you can win out against the entire adult world. They

can hurt you, even kill you, but they can't make you run.

In

1938, stimulated by the example of Superman and Donald Duck,

I began drawing comic books. My first creation was Petie Panda

because pandas were easy to draw and my brother had a stuffed

panda I could use as a model. I worked in black pencil on

white typewriter paper, showing the result to my classmates.

In gradeschool I drew in all about a dozen comic books about

fifty pages each, with colored covers. Only one of them has

survived to this day.

As

a freshman in high school I discovered Fandom, the world of

science-fiction fans. Fandom included many amateur authors

and artists who published, usually by mimeograph, magazines

which they distributed, free of charge, to other amateur authors

and artists. Borrowing my dad's mimeograph, I began publishing

a "zine" of my own, entitled "Universe", followed by another

called "Stupefying Stories", then co-edited with Art Rapp

yet another called "Spacewarp". Meanwhile I also contributed

cartoons and illustrations to many other amateur publications,

eventually being named Number One Fan Cartoonist in "Fanac",

the top newszine in fandom.

As

a college student at the University of Chicago, I contributed

cartoons to the student newspaper and student yearbook, also

producing by silk screen many posters for student organizations

and businesses. Before graduating I transferred to the Chicago

Art Institute, taking the painting and illustration sequence,

but was asked to leave because of my habit of challenging

my instructors.

Abstract Expressionism was the fad of the day, and I attacked

it at every opportunity. (I still think it is a hoax embraced

by snobs who like to appear superior by liking something nobody

else does.) On my last day at the Institute, I defended another

student who was being criticized by an abstractionist instructor

and ended by ducking as the disputed painting sailed like

a Frisbee overhead and crashed into the wall behind me.

Since my expulsion from the Art Institute I have continued

to do cartoons for amateur publications, but have also done

artwork for the Artcraft Poster Company in Oakland, California,

including a prize-winning design for a poster for the "Toys

for Tots" Christmas drive. My work has appeared in trade journals

all over the country and in several "alternate" comic books

including "Alien Encounters Comics", where my story "Nada"

was made into a hit movie for Universal Pictures entitled

"They Live".

Currently I am cartoon editor for a trade journal, "The American

Window Cleaner" and last year was a finalist for the World

Science Fiction Convention's Retro-Hugo trophy for top fan

cartoonist. (I had a heart attack when I didn't win.)

So

other people have their little footraces. I have my cartoons.

Even if nobody else liked them, I would still draw them. Indeed,

I have written two books on cartooning which nobody gets to

read but me. At best it is a satisfying lifestyle, at worst

the cheapest of hobbies. Drawing has the very great virtue

that nobody can stop me from doing it. I can always find an

advertising handout with a blank back. I can always find a

pen, pencil or bit of coal to draw on it with. I don't need

an expensive computer, fancy car, posh office or tailored

suit. I am a worker with his own means of production. I have

a weapon between my ears that I can carry undetected through

any metal detector or customs search.

If I don't like the universe God made, there are billions

of other universes waiting to appear at that point where

my pen meets a blank sheet of paper.

Have

a look at some of Ray's Cartoons

|